Still Wakes The Deep review: soaked in sea horror and shiveringly good voice acting

Oil not sleep tonight

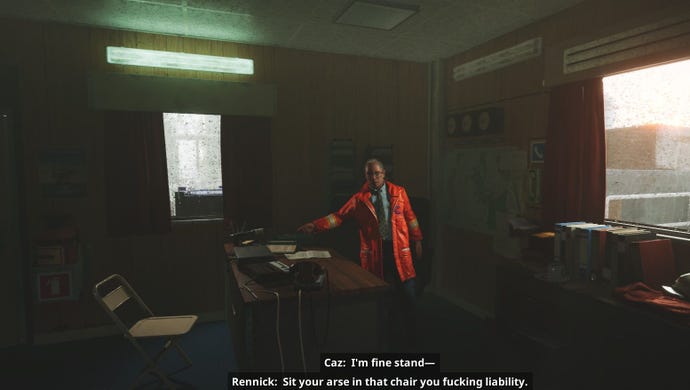

Scottish petrochemical horror is not exactly a genre, but maybe it ought to be. From the opening moments of Still Wakes The Deep you know life on its 1970s North Sea oil rig is precarious. Leaky ceilings, busted panelling, faulty drill machinery - the omens pile up as you spend your first thirty minutes wandering through the colleague-packed canteen and over the platform into the boss' office for a severe dressing-down. It's a classic pre-disaster setup for a mostly traditional monster story, yet the game sticks expertly to the first-person horror form, and its voice actors' performances are so spot-on, that it'd feel churlish to judge this foaming fear simulator for sticking to type. It also has some markedly unsettling use of the shipping forecast, a famously dull feature of British radio I definitely did not expect to freak me out in a video game.

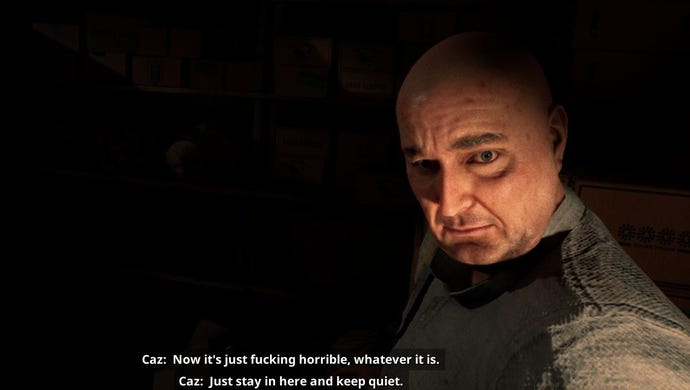

You are Caz, an electrician employed on the Beira D, an oil rig operating in the rainy winter of 1975. Alongside you are a number of fellow workers pushed to the ends of their tethers, patching up the ragged rig with screws and their own unease with bravado and banter. The kind of football-centric chat expected of a mostly male crew in the 70s. Talking to everyone on the rig is like taking an earbath in Scottish slang. Which sounds disgusting when I type it out like that but in reality is a refreshing change from the non-regionalised US chatter that often appears as the main voice in games writing. Scotland doesn't get many hyperlocalised stories like this in our industry (and certainly none this high-fidelity) so it's pleasing for once to hear authentic Glaswegians playfully insulting one another and chatting about the darts, as opposed to the exaggerated facsimile of the same voice frothing out of the mouth of an angry dwarf.

It's also funny to see said slang translated in the subtitles, where "gobshite" becomes "bastard", "rank" becomes "disgusting", and "dinnae flap" turns into "don't panic". At least they didn't try to translate "Buckie" to the plainer "Buckfast" when the infamously violent monk wine gets a namedrop. (If your hankering for authenticity goes further than even reality dictates, there's also an option to play in Scottish Gaelic.)

Of course, everything goes tits-up. Something fleshy and macabre makes its way out of the sea and onto the rig, spreading its tendrils and angry, mother-of-pearl blisters into the supports and corridors. Much of the remaining dialogue might be summarised as [screeches in Scottish], as your crewmates succumb to monsterfication and gory death. An early run-in with one of these monsterpals introduces you to a dedicated "look behind you" button, a terrifying temptation for any horror game enthusiast. I found myself mostly using this to give myself a jolt during chase sequences. But every so often I'd hear a clunk of pipes behind me, or a distant cry, and press the button to glance over my shoulder, only to see nothing. Empty halls. Hollow rooms.

As far as what the game generally feels like to play, its desperate vent-crawling, lever-pulling and locker-hiding put me most in mind of Alien: Isolation. The themes of workers existing in unsafe conditions has definite parallels to the stretched crew of the Nostromo and the broken infrastructure of Sevastopol station. The lifeboats are fitted with crappy cables, broken doors fail to open for trapped engineers, and the rig's foul-mouthed manager insists the monster problem is merely a "minor drill issue" far past the point of catastrophe. Yet unlike Alien: Isolation, it doesn't overrun its horrorspan, taking me seven hours to complete, a good length to maintain fear factor.

That fear doesn't only come from the monsters. The voices and behaviour of the crew are so firmly grounded that when it starts to introduce familiar video game tasks, such as balancing your way across a beam suspended above a raging sea, my seafarer brain said: "Naw mate, naw". In any other circumstance, I would have accepted the bright yellow beam as a passable, expected thing, as common as a red barrel ready to explode. Here, the first time these traversable game obstacles showed up, I felt legitimate anxiety. Caz is not an arms aloft stuntperson, he's an electrician with no experience of such an emergency. When you finally do approach beams, his limits become clear. Caz drops to his knees and crawls across the beams slowly and swearily.

The game loses some of that grounded charm later, by upping the peril to include ridiculous action movie climbing solutions in scenarios where any normal person can spot several safer routes, none supported by the game's pathing. But I can let this go. Vidgam gonna vidgam. Gone are the days when developers The Chinese Room would slap you on a Hebridean island with only the barest guidance. Here the visual language of first-person horror comes through with the clarity required by the medium. Hiding spaces are splashed with helpful yellow paint. Arrows and maps continually mark out your path. When a risky jump is required, it is made obvious. When you need to distract an enemy, there are suddenly tons of throwable objects lying around.

The only time I felt this guidance break down was in later moments when environments became flooded. At some points you are submerged and have to drag yourself along support beams while underwater. At another, you have to find a correct route while your breath quickly runs out. These are probably the most disorienting moments in the whole story and I felt more annoyed by the subsequent drownings than I was frightened. It also suffers from the traditional problem of game horror, in that the tension is broken the more you die. This goes for both rising water and your groaning ex-colleagues.

These tentacled blistermen are not all alike. Each monster you encounter is intentionally and disturbingly named for the person who remains trapped in the hideous schlep of tendons, gristle, and sinew that propels them around. Their behaviour is often similar; they hunt and pursue and patrol. But each feels slightly different. One towers above you on stilt-like legs. Another drags itself about on the floor like a slug. Another will shamelessly enter the vents you hide within, forcing you to be quick and decisive. More disturbing is how each moans in their own way, their pains and problems following them into monsterhood. Some of these things were once your friends, and Caz is continually swearing with horrified pity at them. Others, who were antagonistic to you during the pre-disaster opening, feel even more unmerciful and wretched in monster form. I'm looking at you Addair, you horrible fuck.

It is a great hook. None of the enemies you encounter are faceless baddies. They are familiar, speaking in haunting groans about how they're sorry, sobbing that they miss their mum. They plead with you to help, before assailing you with an agonised wail of rage. One continues to try doing the laundry with infuriated, ineffectual slams of a washing machine door. It's an old theme of horror, that humanity and monstrousness can co-exist within the same body. But again, Still Wakes The Deep carries that trope with such confidence and clarity, it is hard to care that you have seen it before.

And what about Caz, your own character? He is a messer with an upturned marriage and a criminal history, a man who might as well be walking around the oil rig screaming "she's turnt the weans against us" at the hideous fleshhorrors that have taken over. I mean that in a good way. I felt his personal story of love, cowardice and irresponsibility lost some momentum towards the end, when the game starts to rely on well-worn disembodied voices and other weirdness to lean into psychological horror, as opposed to the classic monster movie it otherwise sticks to being. But for the most part he is a good protagonist - out of his depth, troubled, angry and afraid in unequal measure. Like all the others, the voice actor does an excellent job, right down to the harried breathing that kicks in any time a monster comes near you.

The troubles of Caz, like those of others on the rig, feel ordinary against the backdrop of all this horror. And I feel that's the game's great strength - in contrasting the otherworldly shimmering rainbow hellishness of Jeff VanderMeer's Annihilation with the grey pessimism of a Caledonian winter. Caz' personal scramble for survival and forgiveness is just one way in which its disturbing tale can be read. It could also be interpreted as the screeching vengeance of a planet being bled dry. As a lament for the worker who is driven to destruction among the pipes and machinery of capital. As the tragedy that comes of a father's abandonment and thoughtlessness. As a dirge for male friendship, a sorrowful acknowledgment that banter and football is a laughably weak social glue, a mere coping mechanism for the passing down of violence. It is notable that there is one woman on board the Beira oil rig, the engineer Finlay. Depending on your own temperament, it is either her unblinkered resolve or her helpless resignation which eventually cut through the veil of oil, blood, and testosterone.

However you might step away from the rig, I stepped away rattled, impressed, and hungry for more horror as solid as this. It may not revolutionise the genre in any mechanical sense (even that "look behind you" button is something from the Outlast series) but it does set a bar for groundedness and naturalistic voice acting. More Scottish horror? Aye, make it first-person anaw.

This review is based on a review build of the game provided by the developer.